Roxbury Beach (Click most images for larger versions.)

Speaking of Christmas presents.

Speaking of Christmas presents.

A wonderful thing happened in 1924, when I was eleven. For nine-hundred dollars, Aunt Maud bought my family a beach cabin at Roxbury, a small beach community near the tip of the Rockaway peninsula on Jamaica Bay. I think she did it because—although my father (her brother) had abandoned us—she still felt we were "family." At any rate, we loved her for it and immediately began spending warm weekends there, plus all those long, hot, sticky summers of my youth.

The cabin wasn't much, just one big room divided into three sections by half-walls with a walkthrough down the middle. Curtains completed the upper portion of each "wall," and they pulled across the walkthroughs for more privacy. Inside the screened-in front porch was the first section, a big living room with day beds. The middle section was a bedroom with two beds, one against each wall. Behind the bedroom area was the kitchen, which had only a hand pump for water, a small table for meals, and an icebox for perishables. Out back was a small porch with steps down to the boardwalk. Part of it led to the outhouse, which was virtually blocked from view by a riotous growth of shrubs.

But, the cabin's location made it pure gold, and a source of joy for Buster and me. Our summers took on a new promise of escape and repose, our world expanding beyond the blistering pattern of city streets. As a rule, however, our new summers only meant more work for Mother. Especially when we were young, since she had to carry almost everything during the three-plus hour trip to the cabin.

But, the cabin's location made it pure gold, and a source of joy for Buster and me. Our summers took on a new promise of escape and repose, our world expanding beyond the blistering pattern of city streets. As a rule, however, our new summers only meant more work for Mother. Especially when we were young, since she had to carry almost everything during the three-plus hour trip to the cabin.

[Click the image at right for a map of the Rockaway peninsula and the location of Roxbury.]

We would haul as much as we could manage down to the street, board the Flatbush Trolley, and take it all the way out Flatbush Avenue to Jamaica Bay.

We would haul as much as we could manage down to the street, board the Flatbush Trolley, and take it all the way out Flatbush Avenue to Jamaica Bay.

[Picture shows the old Rialto Theater and the Flatbush trolley.]

Then we had to walk a mile along the waterfront to the ferry. It would take us across the bay to the Rockaway landing on Long Island, where New Yorkers went to escape the heat. We, on the other hand, still had another mile to walk down the narrow peninsula to the cabin. During that last mile, I wished for a ferry that went straight across the bay to Roxbury.

It was as if my wish came true when Dad bought his first car. It was so wonderful. All we had to do was load the car and drive to the cabin. Although, I remember driving all the way around the bay, rather than taking the ferry. I guess it was a people ferry, not yet equipped to carry automobiles. Eventually, in 1933, they built a bridge over Jamaica Bay, which made our trips all the easier.

I'm going to take a little detour into the future here, because I think I might have been one of the first persons to walk across that bridge. It happened the night of July 22, 1933, and a boy went with me named Howard Blanke—he had become aclose friend by then, visiting regularly on weekends at the Roxbury bungalow. The reason for our adventure was to see Wiley Post, who had left July 15th for a solo round-the-world flight. He was to arrive that night.

I don't know whether Mother okayed it or didn't know about it, but my guess is I was old enough by then, having just turned twenty, to go whether she liked it or not. Regardless, Howard and I made the long trek over the bay and climbed a low fence onto Floyd Bennett Field just in time to see Wiley land and come rolling in under the spotlights, 50,000 people screaming and hollering. It was an amazing sight. All the people showed up because he had set a new record of seven days, nineteen hours, beating the old record by twenty-one hours. Years later, unfortunately, Wiley and his friend, Will Rogers, lost their lives when their plane crashed in Alaska.

I don't know whether Mother okayed it or didn't know about it, but my guess is I was old enough by then, having just turned twenty, to go whether she liked it or not. Regardless, Howard and I made the long trek over the bay and climbed a low fence onto Floyd Bennett Field just in time to see Wiley land and come rolling in under the spotlights, 50,000 people screaming and hollering. It was an amazing sight. All the people showed up because he had set a new record of seven days, nineteen hours, beating the old record by twenty-one hours. Years later, unfortunately, Wiley and his friend, Will Rogers, lost their lives when their plane crashed in Alaska.

Meanwhile, back in my life, I can imagine Mother's relief as we skirted around the bay or traversed the new bridge, the car loaded to the gills. Yet, even then, summers at the cabin were hard on her. For one thing, all the relatives wanted to visit. We had a stream of "freeloaders"—as she called them when she had had enough—coming and going and placing demands on her, either real or imagined. But, I think it was partly her fault, since she didn't know how to relax when she had company. That must be where I got it!

Buster and I didn't care, though, because it meant playmates we knew. We liked it when company came: aunts, uncles, relatives and friends. Ike's first son, Billy, was one of those visitors, he and his best friend, Howard Blanke.

Billy's full name was William Thomas Hillis. He was born in 1910 to Ike and my father's sister—my aunt—Martha Guy, but she died in childbirth. So, Ike and Billy moved in with her sister, my Aunt Maud, and they lived on 103rd Street in Manhattan just east of, you guessed it, Columbus Avenue. The friend, Howard, actually did live on Columbus, a block north of 103rd.

Billy's full name was William Thomas Hillis. He was born in 1910 to Ike and my father's sister—my aunt—Martha Guy, but she died in childbirth. So, Ike and Billy moved in with her sister, my Aunt Maud, and they lived on 103rd Street in Manhattan just east of, you guessed it, Columbus Avenue. The friend, Howard, actually did live on Columbus, a block north of 103rd.

[Picture of Billy Hillis at his high school graduation. Click for larger version.]

I think we started calling Buster "Buster" because of Billy. You see, there wasn't another Billy around before Buster went to Ireland, so the odds are good we probably called Buster Billy then. And that would explain why Captain Cumiskey didn't remember the nickname "Buster"; he remembered "Wee Willie" or maybe "Wee Billie?" But there was another Billy when Buster returned, so that must be when we began calling him differently. Besides, I liked it better than Billy, always have. My brother looked like a Buster.

At any rate, Billy and Howard were most comfortable with Ike. Originally, I think they only came out whenever Aunt Maud did, but after Billy began living with us and after Ike got a car, Howard came out with Ike. I'm talking about the summers, when Ike still worked, but the rest of us lived at the cabin. Then, on Saturdays, Howard would meet Ike at the Railway Express Agency. By then Ike was foreman of the garage of battery-operated, electric delivery vans, and after he checked to make sure everything was okay for Monday morning, they would get in the car and ride down to Roxbury. When they got there, Howard would always help Ike cover his precious car with a large tarpaulin to protect it from the sun and sand, until they went back on Monday. I don't remember Howard ever staying for more than a weekend, but I could be wrong. I do, however, remember all of them pitching lots of horseshoes.

Ike, Billy, and Howard, plus any other male guests who showed up, used to throw shoes continually, and Ike, especially, was an excellent shoer, often making double ringers. I can still here the clanging and yelling. In a recent letter from Howard—we're still in contact after all these years—he talked about the horseshoe tossing, but then also revealed a much different picture of Ike from mine.

Ike, Billy, and Howard, plus any other male guests who showed up, used to throw shoes continually, and Ike, especially, was an excellent shoer, often making double ringers. I can still here the clanging and yelling. In a recent letter from Howard—we're still in contact after all these years—he talked about the horseshoe tossing, but then also revealed a much different picture of Ike from mine.

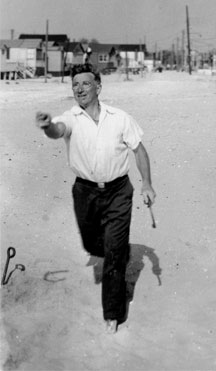

[Picture is of Ike pitching horse shoes at Roxbury. The image is full sized.]

The Ike I knew was very strict, almost tyrannical, and quick to scold and chastise. He took out his frustrations on me. He often hit me, and I saw him hit Mother. I didn't like him very much. It's true that he mellowed with time, but I never saw the man Howard recalled. According to Howard, Ike was a devout Protestant, a good man, a good father to Billy, and a Mason. When my oldest girl, Christine, wanted to join Job's Daughters, we asked Ike to sponsor her, because he was the only Mason we knew. Howard also said he witnessed Ike kneel by his bed on occasion to say his prayers at night.

It leads me to believe that the man who lived with Maud was happier than the one who lived with us. Of course, whereas he was fastidious—or as we'd term it nowadays: anal retentive—I was a handful, always in trouble, doing what I felt like doing, and not eager to jump at anyone's call. So, it's possible Ike disliked me partly because of that, because I didn't fit into his neat, ordered, and conservative world...and because I wasn't his child.

He probably prayed at night to be rid of me!

Anyhow, when Howard mentioned the sounds of the horseshoe pitching, it also reminded me of the booms we heard from Fort Tilden. It was gunnery practice, and big guns fired out over the Atlantic, plus anti-aircraft weapons at targets towed by planes. Since they were only about a mile away, the repercussions rattled our windows and knocked dust from the rafters. That's when the children would all run for the water: the booms didn't bother you so much when you were splashing and swimming in the ocean.

As you can see, for us, the fortunate children who played summers away, company meant more fun, more friends, and more family. And they also made it easier to slip away and get out of chores. We anticipated visits. Mother, however, as she confided to me later, wished they would stay away. She wanted more than anything else to sit, put her feet up, and do nothing for a change. Poor Mom, it seldom worked out that way. Instead, I'm afraid it was just one thing after another for her.

The kitchen was smaller and had less amenities than the one at home, and yet she usually had more mouths to feed. The other women would offer help, but Mother took on so much herself, uncomfortable with asking for or even accepting help from her guests'.

The kitchen was smaller and had less amenities than the one at home, and yet she usually had more mouths to feed. The other women would offer help, but Mother took on so much herself, uncomfortable with asking for or even accepting help from her guests'.

[This picture is of Mother and Aunt Maud, our benefactor, taken in Roxbury's ubiquitous shrubs—they were always used for photo backgrounds. Click the image for a larger version.]

A trip to the market—which we did often since things didn't last as long as they do today, plus the ice box was tiny—took most of a morning. Mother would drag us, her little beasts of burden, to the bus, which we rode up to the market in Rockaway. After the shopping; Buster and I would carry what little we could, while she hauled the rest back on the bus. The hardest part came at the end of the bus ride: the sun-baked sand. We had to lug the groceries across yards and yards of soft, burning sand, which made walking laborious. We were already hot, cranky, and tired.

My young legs and feet worked so hard churning through that deep sand. I can still feel the pain as we lugged the groceries over that last arid-stretch toward the cool ease of the boardwalk—I've liked boardwalks ever since. The boardwalk signified not only an end to the taxing sand, but also that the cabin was close, the end of our journey near. The relief I felt, when we finally stepped onto the wood, was heavenly.

The boardwalks connected the rows upon rows of cabins in all the small beach colonies along the peninsula, colonies with names like Breezy Point, Belle Harbor, Seaside, Neponsit, Averne, and, of course, Roxbury. They were strung out along a finger of land known as the Rockaways, which separated Jamaica Bay from the Atlantic Ocean. Our cabin was three rows back on the bay side. If we wanted to get to the Atlantic, or the Big Beach as we called it, we had to walk across the peninsula, which meant trespassing on U.S. military property.

To get to the Atlantic, we would duck under the fence surrounding Fort Tilden, a U.S. Army base that was part of the harbor defense system. I don't think the Fort personnel were very good, though, because we never got caught in all the years we ducked under their fence and crossed their property. When we were small, Bus and I didn't venture to the Big Beach as often, because the waves were so monstrous. We would only watch the huge breakers crash on the shore. As I got older, though, I learned to dive under those same waves, going deep so that the churning water couldn't suck me up and tumble me around till my lungs were ready to burst. I loved it.

The water was calm and warm on the bay side of the peninsula, with waves children could deal with; better suited to sinkable tikes. So, that's where we spent most of the time during our first few summers.

There were two piers about a quarter mile apart on that beach. I began my water education by jumping off the pier nearest us, then frantically dog-paddling to the safety of the exit ramp, which dipped down into the water. Initially, I was scared out of my wits. I flailed wildly, holding my breath, eyes wide, struggling to reach the ramp. But, because it made me feel so grown up, I kept at it. I can admit now that I also did it to showoff to those too afraid to jump, many of who were older than I.

There were two piers about a quarter mile apart on that beach. I began my water education by jumping off the pier nearest us, then frantically dog-paddling to the safety of the exit ramp, which dipped down into the water. Initially, I was scared out of my wits. I flailed wildly, holding my breath, eyes wide, struggling to reach the ramp. But, because it made me feel so grown up, I kept at it. I can admit now that I also did it to showoff to those too afraid to jump, many of who were older than I.

[Yes, that's me showing off for the camera on Roxbury beach (the houses near the shore are always bigger than the ones farther back...even today.)]

It seems like I was always doing something to prove my worth, although I didn't look at it that way at the time. It's possible, on a subconscious level at least, that I was aware of my lower status, or maybe not. Maybe my "grown-up" mind is merely wrestling with itself, applying canned labels to unexceptional events.

Anyway, I gradually learned how to swim that way—jumping in, pulling for safety—and how to dive. Before I left Brooklyn for California, I was diving off the high perch, then plowing through the water from pier to pier and back, doing "laps" with the rest of the accomplished swimmers.

I think those idyllic summers engraved a love of the ocean upon my soul. It became so many things to me: a constant source of awe and inspiration, a friend and "foe," a thundering threat and an endless playground, a calming rhythm and an exhilarating attack. I wouldn't want to live without it.

Roxbury, however, also held darker etchings. For instance, one summer, before I learned which kids to trust and which to avoid, I fell in with a bad crowd. They were a gang of teenagers that hung out together during the summer, and one day they asked me to join them. A girl I'd met told me they'd come by after dark and we'd have some fun. I felt an uneasy excitement, not knowing what to expect.

That night when I heard her call, I went outside and down the cabin steps to where they waited. There were low whistles, and I was aware of their eyes passing over my blue linen dress [That's it in this photo of Mother and me, taken at Roxbury. Click it for a larger version.]. I smiled, uncertain, a little embarrassed, unfamiliar with such open displays, and discomforted to learn that I was the youngest one in the group. I felt a small constriction of fear in my chest.

That night when I heard her call, I went outside and down the cabin steps to where they waited. There were low whistles, and I was aware of their eyes passing over my blue linen dress [That's it in this photo of Mother and me, taken at Roxbury. Click it for a larger version.]. I smiled, uncertain, a little embarrassed, unfamiliar with such open displays, and discomforted to learn that I was the youngest one in the group. I felt a small constriction of fear in my chest.

The girl introduced me to the others, and they started calling me Venus. (At the time, I didn't understand the reference.) But, it made me feel awkward, plus a stab of concern about being the new member, not knowing how to act, nor what to expect. I wanted to be accepted, but at what price?

"Where are we going?" I asked, as we moved off down the row of cabins.

First, no one said anything; there was only some sniggering.

"To the church," one boy finally said.

I sighed. The uneasy feeling, like a tight band around my chest, eased. Nothing could happen at a church, I told myself.

I remember the dark shape of the steeple rising from the shadow of the dunes but, as we drew closer, I saw that the windows were dark. The uneasy feeling returned, although I rationalized that we could be early for a meeting. When someone switched on a flashlight, however, and the group began to slip around the side of the building; I knew I was wrong.

A chill ran through me as I watched other couples stoop down, then squirm in under the church. I was the only one left standing when the flashlight went out.

"Relax, Venus," my "companion" said, grabbing my hand and pulling me down toward the crawl space. "Come on in; the water's fine."

His words evoked insinuating laughs from under the church. I could hear whisperings and the settling of bodies, and then the quiet expectancy, which the clink of a glass bottle shattered.

"O God in heaven," I thought to myself, "is this their idea of fun?"

Suddenly, I broke free from the boy and ran as fast as I could over the sand towards home. My pounding heart deadened the crude, boisterous laughter. Relieved to get away, I didn't care what they thought. I just wanted to get back to the safety of my cabin and the security of my convictions.

The impressions of that night, however, have stayed with me to this day. In a college writing course, I wrote a story about the experience—the teacher liked it so much he read it to the class. During the discussion that followed, one woman felt that scares like that are what decide our values. When confronted with the same situation, how would others respond? Do situations that happen to us define who we become or is it all hereditary, already in us? My opinion changes from year to year.

All in all, though, my impressions and memories of Roxbury are invariably blessings, magical days of sun and sea and friends and family; not to mention, my first taste of employment, making money!

All in all, though, my impressions and memories of Roxbury are invariably blessings, magical days of sun and sea and friends and family; not to mention, my first taste of employment, making money!

I got my first job the summer I turned twelve. It was as a helper (I wasn't really a waitress) for a clam stand on the Big Beach. By then Fort Tilden had been decommissioned and part of it turned into Jacob Riis Park, and that's where the stand was. It was easy work, serving customers their fish and clam sandwiches and drinks, but it felt so good to contribute. The extra money went to my mother and helped to make ends meet.

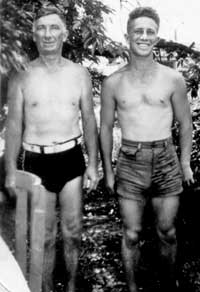

[This photo of Ike and my half-brother Harry was taken during the time I was working for the bank. Click it for a larger version.]

For us, family members expected to work and contribute to the upkeep of the home. I didn't question this assumption; I enjoyed it. Buster began full-time employment after the eighth grade. I know he didn't enjoy that as much as I enjoyed serving sandwiches on the beach (his jobs were much harder), but we didn't feel deprived. Working was an honorable pursuit, and we were grateful when we had a job.

As I got older, I took summer jobs in the city, which meant I commuted to Roxbury—I didn't like it as much as the clam stand, but the larger paydays helped soothe my disappointment.

Let's see, one summer I was a clerk at a five-and-dime; another, I worked as a typist; and yet another, I worked for a bank; and so it went. Here again, I thrived on the sense of accomplishment. In fact, the bank liked my work so much they asked me to stay on after the summer but, much to my dismay at the time, Mother insisted I finish high school. As I said, at the time I didn't understand why Buster could work, but I had to go to school. I'm very thankful, now.

Still, the thing I remember most about those summer commutes, was the relief from the heat when I got to the beach. I'd be into my suit and into the water in a heart beat, sighing as the sweat and exhaustion washed away. For me, the saltwater had almost miraculous rejuvenating powers. As it worked, I would tread chest deep, my toes bouncingly supporting me, listening to all the different sounds and watching the sky as my mind cleared and my spirits soared. Then, I would dive under and glide through the water. It felt like flying. Wonderful.

Still, the thing I remember most about those summer commutes, was the relief from the heat when I got to the beach. I'd be into my suit and into the water in a heart beat, sighing as the sweat and exhaustion washed away. For me, the saltwater had almost miraculous rejuvenating powers. As it worked, I would tread chest deep, my toes bouncingly supporting me, listening to all the different sounds and watching the sky as my mind cleared and my spirits soared. Then, I would dive under and glide through the water. It felt like flying. Wonderful.

[Here's a map that lays out our Flatbush route, the peninsula, Brooklyn, and much more. Click it for a larger version.]

At any rate, during all my summers staying at the cabin, the weekends were the best. That's when family and friends would stay, and we would laugh and play, then wind things up with our traditional big Sunday night feast. Those meals were the highlight of each week. Not only was the food good and plentiful, and the conversation loud and filled with laughter—Howard used to walk to the pier to buy pitchers of beer for the adults—the dinner also signified Ike's departure since he needed to get up early Monday. Mother, too, seemed to enjoy the dinners for a similar reason: everyone left after our Sunday night repast! Meaning, Monday would be her day of rest.