Isabelle: The Early Years (Click most images for larger versions.)

Call me Isabelle.

My full name is Isabelle Mary Josephine Guy Simmons Gessford, but no one calls me that. My friends call me Belle. Some East Coast relatives call me "Is." My four children call me Mom, and their children and their children's children call me Grandma Belle. No one ever called me Mary, well except for an irate Mother as in, "Isabelle Mary Guy! Stop that right now!" And as I recall only one nun ever called me Josephine, my confirmation name. I think of myself as Isabelle, so call me that.

I entered this world kicking and screaming, as they say, on July 6, 1913.

I found myself in a hot, humid bedroom at 72 West 106th Street on the Upper Westside of New York City, in what they call Manhattan Valley due to a slight depression there. My first memory of that small walkup is standing in a dark hallway, listening. It was night, probably after my bedtime, and I was listening to my mother and father talking in the kitchen. Unaware of me, they spoke in subdued voices, but voices filled with much gravity and emotion. For some reason their tone filled me with apprehension. Even though I was only three at the time, I knew something was wrong.

And something was wrong: my Father was saying goodbye; he would leave my mother, my brother, and me for a dark Italian adulteress. I didn't know he could do that: leave. It threw me off balance, destabilized my world. Later, however, I realized that his departure made me stronger: I learned to rely on myself because others might leave.

Today, were I to list the lessons life taught me at an early age, self-reliance would be at the top. Of course, it must have topped such a list for many Irish in the New World: we had to fend for ourselves. Actually I guess, in his own way, Father was fending for himself, too, just not in a way acceptable to the rest of us. Which reminds me that another trait his departure instilled in me was loyalty: a stubborn refusal to let anyone down. So, though it sounds strange to say it even now, a lifetime later, Father's desertion was good for me, just as it turned out to be good for him—he had a full, prosperous life. The one who suffered was Mother.

Both my parents were Irish immigrants—Margaret Campbell, born March 6, 1889, in Termonfeckin, County Louth; and William Wellington Hosford Guy, born July 8, 1888, at Crannogue, County Tyrone, in what we call today Northern Ireland. (He and I almost shared the same birthday, but I guess I couldn't wait.) They met in New York City while William resided on Columbus Avenue, and Margaret on West 104th Street, in what must have been an Irish neighborhood.

Despite their expectations and the assurances of those who went before them, neither of my parents felt welcomed in the New World, other than by relatives who preceded them. Even other "micks" could be jealous and distrustful, afraid of losing opportunities to the Johnnies-come-lately. To native-born New Yorkers, the WASPs of that era, my parents were outcasts, lowest of the low, and everything about them—speech, mannerisms, clothes, religion, lack of education, lack of status—increased the barriers.

At any rate, in what was probably a subdued ceremony, William and Margaret were married October 25, 1911 at the Ascension Catholic Church on W. 107th Street, by Father Matthew J. Duggan—an all Irish wedding. Mother's oldest sister, May Campbell, signed the marriage certificate as one witness, and a Peter Hagan as the other. I have no idea who he was, but considering the absence of his name in my history, I think it's safe to say he was one of Father's friends.

Then, my parents began their life together in an apartment on West 92nd Street, and about four months later, on February 11, 1912, the reason for their low-key wedding became clear: my brother, William Thomas "Buster" Guy, was born. (Thomas was my father's father's name.)

Perhaps the seeds of Father's abandonment took root in that inauspicious beginning. Did he feel an obligation, rather than affection toward my mother? I don't know. Either way, he left us sometime during 1916 and moved to Connecticut to live with his "hot, dark Italian mistress" (that's how my family always portrayed her). He chose Connecticut because, due to that state's laws, he didn't have to pay alimony nor child support. So, the abandonment was complete: physical, emotional, and financial.

Perhaps the seeds of Father's abandonment took root in that inauspicious beginning. Did he feel an obligation, rather than affection toward my mother? I don't know. Either way, he left us sometime during 1916 and moved to Connecticut to live with his "hot, dark Italian mistress" (that's how my family always portrayed her). He chose Connecticut because, due to that state's laws, he didn't have to pay alimony nor child support. So, the abandonment was complete: physical, emotional, and financial.

(I've often wondered what did bring about my parents split. Mother could be a hard woman, solemn and, as I remember her, also timid when confronted. But, I don't know whether those traits were innate or a result of losing her husband, or caused by her second marriage (I remember her timidity with her second husband, a very hard man to please). I guess it's possible that the fiery Italian temptress attracted Father because she was so much the opposite of his wife, a drab, homely woman. I can't remember what Mother and Father were like together, whether they fought or ignored one another, or whether they had some genuine feelings for each other; my only memory while they were still together is the conversation. Yet, I'm sure that witnessing Mother's subsequent years of hardships, after he left, had a lot to do with my inability to forgive Father until years later.

You see, back in 1907 my mother received money and sponsorship from relatives already in the States (her sister, May, and brother, Patrick, included—both having made the trip in a similar manner) so she could depart Ireland for the American Dream. Unfortunately, this frightened, homesick eighteen-year-old soon discovered that her "dream" wouldn't be her reality, and by the time Father left, it was just one more nail in the coffin.

Not only was Mother poorly accepted, but life in New York City was fast, loud, dirty, alien and intimidating. It was nothing like her tiny, placid Irish hamlet of Termonfeckin (Tearmann Feichin or "Sanctuary of St. Feichin's"). That rustic village sat in a wooded dip only a half-mile from the Irish Sea, with nothing but a small tower-house castle and a rare tenth-century high cross to distinguish it from any other village in County Louth.

Not only was Mother poorly accepted, but life in New York City was fast, loud, dirty, alien and intimidating. It was nothing like her tiny, placid Irish hamlet of Termonfeckin (Tearmann Feichin or "Sanctuary of St. Feichin's"). That rustic village sat in a wooded dip only a half-mile from the Irish Sea, with nothing but a small tower-house castle and a rare tenth-century high cross to distinguish it from any other village in County Louth.

In "New" York, she discovered that work—when and if you found it—was demanding and demeaning. She had to labor long, backbreaking hours with little compensation. She told me, when I was older, that her station in New York felt lower than it had in Ireland, and she so missed the greenery and fresh air. Gone were the verdant fields that surrounded Termonfeckin, gone its clean sea breeze, its soft silence, as well as her family and friends. She was very lonely.

It's hard for me to imagine what it must have been like for Mother, although in a way I did the same thing, just in reverse: large city to small town. I, however, had the love of my life to share that adventure with me. Mother came to the New World afraid and alone—despite marriage and children I think she was afraid and lonely every day of her life. It got so bad she almost went back to Ireland. In fact, she confided in me that she would cry herself to sleep, dreaming of going back. In the end, I think her stubbornness prevented it. That, and after much struggling, she finally landed what everyone concluded was a plum position: live-in house servant for Enrico Caruso, the world famous Italian tenor! But, the job didn't turn out to be a "plum" or so Mother let on.

Caruso died in 1921 at Naples, Italy, after a long, extracted, bed-ridden stay at New York's Vanderbilt Hotel on Park Avenue. By all accounts he was an amiable, even sweet man, considerate and generous, but Mother implied something else. Though she never talked about her experiences with Caruso, it was obvious she held him in low esteem. Her sisters tried to drag from her the details of life with the celebrity, but she would only admit that she wasn't happy working for him due to the way he treated her—Irish bigotry? That was it, but for years after leaving his employ, whenever one of his records played, or his name came up in conversation, she would make a derogatory sound and say, in her heavy brogue:

"Caruso, humph, he was nothing."

"Caruso, humph, he was nothing."

But, she would never add to that tantalizing statement. If pressed, she would simply wave her hands and walk away, saying, "Enough said." (That's how the phrase entered my lexicon: enough said.)

I've harbored the idea that her dislike of the man was partly due to his ethnicity—same as the house wrecker's! Nonetheless, I've often wondered what she might have written had she kept a diary. I've regretted not wringing it from her before she left.

Before all that, and immediately following Father's departure, Mother felt she had only two choices: go back to Ireland or stay and find a new husband. Despite her nostalgia and twinges of homesickness, the stark realities of life in Ireland, plus the scarcity of eligible bachelors in Termonfeckin, decided things for her. I imagine that her Irish obstinacy again came into play: she wouldn't want to admit defeat. So she stayed, but another problem was, she didn't have the means to live, support her children, and simultaneously hunt for a hubby.

The solution she came up with was to place Buster and me in the care of family back in Termonfeckin. That was her plan, so to Ireland we went.

I was amazed when our pony cart jostled down that muddy country lane.

For a three-year-old who had never left the City, everything was so green and open. Fields went off in every direction as far as my little eyes could see. Sheep wandered over them and over the road. I couldn't believe there was a town at the end of that small, rutted path; and there wasn't, at least not anything I would have called a town. For Termonfeckin was just a smattering of small cottages and moderately bigger commercial buildings crouched at a crossroad in the middle of that sea of green, with two church steeples set at opposing ends of the village reflecting the schism in the country.

I remember thinking, "This is it?" Being only three, I wanted to go back to the ship we'd come on, so I could get more ice cream! It so impressed me, that the ice cream is the only memory I still have of the voyage across the Atlantic. Lots and lots of ice cream.

"You scream. I scream. We all scream for ice cream."

(I learned years later, back in the States, that the Irish Sea was less than a mile along the road to Clogher Head, but we never went to see it—I wonder now whether the Irish Campbells did not have the love of the sea that has gripped me so completely during my life.)

By the time we arrived in Termonfeckin, however, the once grand Campbell clan had withered. Only my mother's "ma" and her two children, the ones who had not yet made the great escape to America, were still living there: Grandma Mary, Essie and Laurence. There was another sibling, Willie, who had left for the States, didn't like it, returned to Ireland and joined the British Navy, so he no longer lived in Termonfeckin. My mother's father, Patrick Senior, had died in 1915, a year before our arrival, but not before he had purportedly lost the family farm in stereotypical Irish-drinking fashion. Whatever the case, when our pony cart arrived in Termonfeckin that day, Grandma Mary resided with the remnants of her children and dreams in one half of a small duplex.

By the time we arrived in Termonfeckin, however, the once grand Campbell clan had withered. Only my mother's "ma" and her two children, the ones who had not yet made the great escape to America, were still living there: Grandma Mary, Essie and Laurence. There was another sibling, Willie, who had left for the States, didn't like it, returned to Ireland and joined the British Navy, so he no longer lived in Termonfeckin. My mother's father, Patrick Senior, had died in 1915, a year before our arrival, but not before he had purportedly lost the family farm in stereotypical Irish-drinking fashion. Whatever the case, when our pony cart arrived in Termonfeckin that day, Grandma Mary resided with the remnants of her children and dreams in one half of a small duplex.

The village of Termonfeckin, County Louth, sits on the eastern seaboard of Ireland about thirty miles North of Dublin and, according to a signpost, eight kilometers northeast of Drogheda. Questions arise when dealing with place names around Termonfeckin because it's more than just that village. The name Termonfeckin also applies to a civil parish, a Roman Catholic parish, a district electoral division, a townland, and the actual town center which is referred to as Termonfeckin Town in the 1901 Irish census. And, that's why you'll keep seeing things like: Newtown, Termonfeckin. (Basically, I take that to mean Newtown is in the civil parish of Termonfeckin.)

(There's an old Philip and Sons map of County Louth, which depicts some of these divisions HERE.)

To help avoid even more confusion, here is a breakdown of the land divisions:

• County Louth has two parliamentary divisions: North and South Louth; Termonfeckin is in South.

• Then you have District Electoral Divisions; Termonfeckin's is called Termonfeckin.

• Louth is also broken into several baronies; Termonfeckin is in Ferrard, the sourthern most.

• There is also something called the Poor Law Union, where Termonfeckin falls in Drogheda.

• Then, of course, you have Termonfeckin parish, both lay and secular.

• And last but not least, the Townland of Termonfeckin.

Other "townlands" within Termonfeckin's umbrella (whichever one you choose) are Termonfeckin Town, Newtown, Baltray, Betaghstown, and others. (Those being mentioned in my genealogy.)

And I hope that helps!

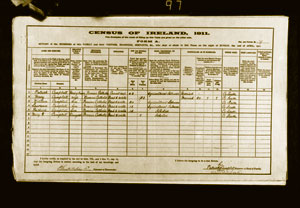

In the 1911 census, the Campbell clan lived in House Number 39 in Termonfeckin, not Termonfeckin Town, but I can only guess at what "town" represents: town center? In that census, a short five years before my visit, there were still six Campbells living at home: Father Patrick (68), Mother Mary (52), 20-year-old William, 18-year-old Lawrence, 12-year-old Richard, and little Mary E. (Essie) who was 7-years old.

In the 1911 census, the Campbell clan lived in House Number 39 in Termonfeckin, not Termonfeckin Town, but I can only guess at what "town" represents: town center? In that census, a short five years before my visit, there were still six Campbells living at home: Father Patrick (68), Mother Mary (52), 20-year-old William, 18-year-old Lawrence, 12-year-old Richard, and little Mary E. (Essie) who was 7-years old.

[Click the image for a pdf file of the census which can be enlarged a lot.]

On a personal note, the census doesn't clear up the spelling of Laurence's name as Mr. Behan, the man who took the census, wrote the name in such a way you can read it as "Lawrence" (which today's archivists did while transposing the name to the Irish Archives website) or Laurence, which is how I always saw it written—although the family mostly referred to him as Lar.

Also in the census, all the Campbell men were designated "Agricultural Labourers," except for young Richard who, along with Essie, was called a "Scholar." In another column titled: Completed years the present Marriage has lasted, the number is 28, which means Patrick and Mary married in 1883. The National Archives say it will post the 1901 census soon, and I can only guess where the Campbells were then; did they still have the farm? (I'll add to this when the information is available.)

As for me, there are only brief scenes and flashes of Termonfeckin left in my memory. Really, the only clear, lasting impression is the cloying stench of constantly boiling potatoes. It permeated my grandmother's house. The smell was in the wooden beams and floorboards, the linens and curtains, my bed clothes, even my hair! I quickly learned to loathe the reek. It nauseated me. When I discovered that Mother meant to return to New York City without Buster or me, my determination not to be left behind was in large part due to that horrible odor.

Once I did realize what was going on I made it known most vociferously, with the obstinacy and immediacy only a child can muster, that I wasn't staying in Termonfeckin—over the years, Mother never tired of telling the embarrassing story about how I threw fits to get my way. At any rate, after all the tantrums I'm not sure whether Mother relented or the Campbells refused to let me stay. Either way, I went back to New York while poor Buster, not as strong-headed nor leather-lunged as I, remained in Termonfeckin. (I remember being excited at the prospect of more ice cream, although the rest of the trip back is a blank.)

Once I did realize what was going on I made it known most vociferously, with the obstinacy and immediacy only a child can muster, that I wasn't staying in Termonfeckin—over the years, Mother never tired of telling the embarrassing story about how I threw fits to get my way. At any rate, after all the tantrums I'm not sure whether Mother relented or the Campbells refused to let me stay. Either way, I went back to New York while poor Buster, not as strong-headed nor leather-lunged as I, remained in Termonfeckin. (I remember being excited at the prospect of more ice cream, although the rest of the trip back is a blank.)

Before we left, however, a Wm. Dobkin took a picture of Buster and me sitting on an old, carved wooden bench, possibly a studio prop. But I don't remember it. I don't remember posing like that with his arm so protectively around me, but the picture speaks volumes about the emotions we were feeling. Mother told me years later that she wanted the photo as a memento of her two children, toward the day when they would be together again. No one knew then when that would be.

It was a tearful, heart-wrenching departure. Buster didn't want to stay either, but he hadn't been capable of convincing Mother not to leave him. I think he was too gentle a soul to make a fuss, plus Mother thought it would be easier for her and I, two females, to live together, cheaply. Whichever reason, Buster stood crying on the stoop, Grandmother holding his hand, as Uncle Laurence drove Mother and me off in the creaking pony cart to the train station in Drogheda. It would be five years before I would see Buster again.